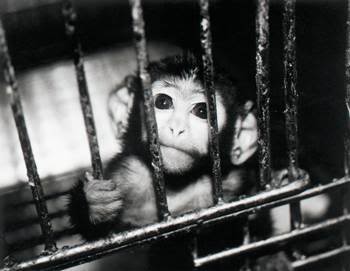

Mice, rabbits, rats, beagles, geese, and other animals all show measurable physiological stress responses to routine laboratory procedures that have been up until now viewed as relatively benign. The findings come in a new report published in Contemporary Topics in Laboratory Animal Science, based on an extensive review of the scientific literature by ethologist Jonathan Balcombe, Ph.D., of Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM). For example, a mouse who is picked up and briefly held experiences several physiological reactions. As stress-response hormones flood the bloodstream, the mouse exhibits a racing pulse and a spike in blood pressure. These symptoms can persist for up to an hour after each event. Immune response is also affected. In rats and mice, the growth of tumors is strongly influenced by how much the animals are handled. Dr. Balcombe’s paper will appear in the journal’s Autumn 2004 issue, expected in late November.

Mice, rabbits, rats, beagles, geese, and other animals all show measurable physiological stress responses to routine laboratory procedures that have been up until now viewed as relatively benign. The findings come in a new report published in Contemporary Topics in Laboratory Animal Science, based on an extensive review of the scientific literature by ethologist Jonathan Balcombe, Ph.D., of Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM). For example, a mouse who is picked up and briefly held experiences several physiological reactions. As stress-response hormones flood the bloodstream, the mouse exhibits a racing pulse and a spike in blood pressure. These symptoms can persist for up to an hour after each event. Immune response is also affected. In rats and mice, the growth of tumors is strongly influenced by how much the animals are handled. Dr. Balcombe’s paper will appear in the journal’s Autumn 2004 issue, expected in late November.

Until now, humane concerns focused mainly on the experiments themselves. The new findings suggest that routine procedures, such as blood draws and use of stomach tubes, are terrifying for animals. “In essence, there is no such thing as a humane animal experiment,” says Dr. Balcombe. “Fear or panic ensues when the animal is touched or stuck with a needle.”

The paper, a review of 80 previously published studies, is titled, “Laboratory Routines Cause Animal Stress,” and focuses on three routine procedures: handling, blood collection and force-feeding. Independent of the invasive experiments themselves, these daily routines can cause an animal to experience elevated bloodstream concentrations of corticosterone, prolactin, glucose, and epinephrine, all indicators of stress. Impaired immune response has also been recorded in animals after anxiety-producing contact with lab personnel.

“Research on tumor development, immune function, endocrine and cardiovascular disorders, neoplasms, developmental defects, and psychological phenomena are particularly vulnerable to data being contaminated by animals’ stress effects,” notes Dr. Balcombe.

Dr. Balcombe’s study follows closely a recent paper in the British Medical Journal, titled “Where Is the Evidence that Animal Research Benefits Humans?” The authors found that in many cases trials on humans were conducted concurrently with the animal studies and in other instances, clinical trials went ahead despite evidence of harm from the animal studies.